Introduction

Offensive Security Tools are any kind of functionality meant to facilitate intrusions and security bypasses in order to achieve the former.

- Close Source Tools: The most infamous example is CobaltStrike.

- Open Source “as is” Standalone Tools: Metasploit, Mimikatz, and various RAT/C2 frameworks are some examples.

- Open Source Libraries: Examples include some memory injection libraries and other offensive libraries which must be incorporated in a tool in order to be useful.

Unsophisticated actors adopt OSTs to fill in R&D resources which they don’t possess while advanced actors, including government-backed ones, incorporate OSTs so they can spend their resources elsewhere in advancing operations or upgrading infrastructure, for example.

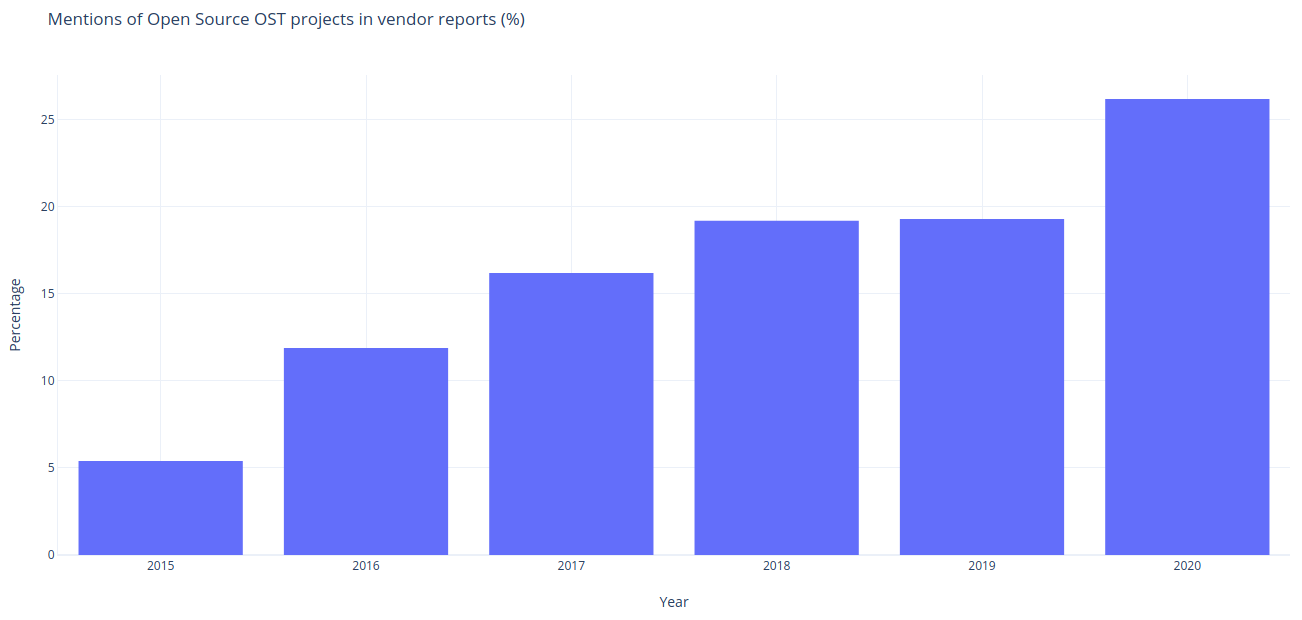

We analyzed thousands of threat actor reports from security companies dating back to 2015, checking for their references to open source OST projects. What we found is the number of references to open source OST projects is steadily on the rise which indicates their increasing usage.

What is special about OST libraries is they can’t operate independently and must be included as part of a bigger tool. These embedded libraries are rarely documented by security companies due to the difficulty it takes to identify them, as they are only part of a malicious file and usually stripped of strings.

The ability to detect files that use offensive libraries can enhance threat hunting capabilities as very few legitimate programs will include such functionalities.

In this article we will present a tutorial on how you can create code-based YARA signatures to find malware using OST libraries.

This article is a part of a larger investigation into the effects of free publication of OSTs. The full research will be presented at VirusBulletin.

Malware Adopting Open Source

Malware developers aren’t much different from normal programmers in that they both want to do their job in the easiest way possible. For some tasks, the most efficient solution is to simply copy and paste code from the Internet. If malware developers take this short cut when developing their tools, we as defenders should take advantage of it.

During our investigation, we identified which open source OST libraries threat actors most often copy and paste into their toolsets. One conclusion we drew is that many actors outsource memory injection logic into a small subset of open source libraries.

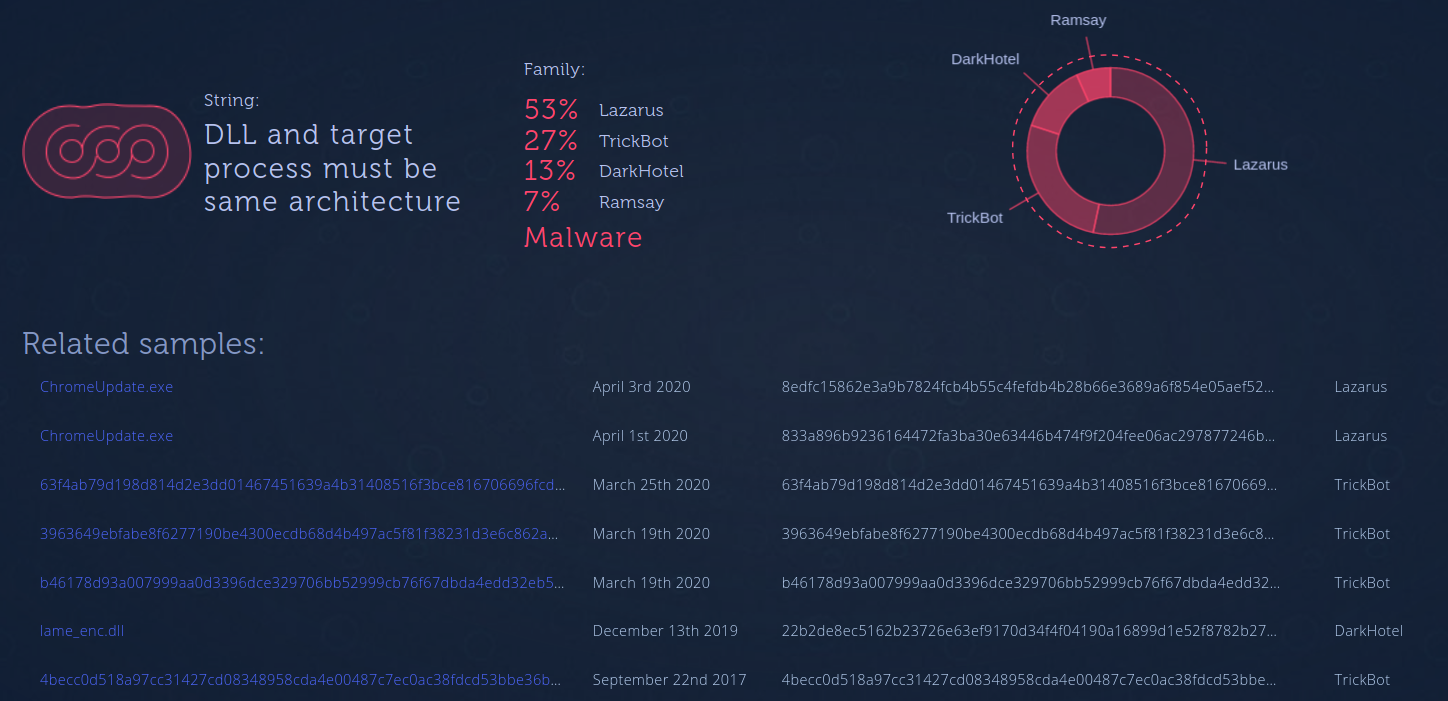

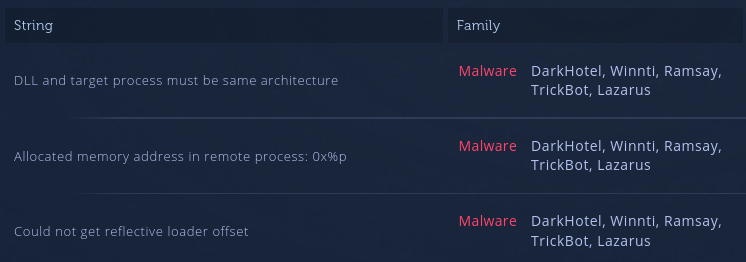

As an example, using only string reuse, we can observe that Lazarus, Winnti, Trickbot, Ramsay, and DarkHotel all have used the ImprovedReflectiveDllInjection library:

(‘Search Exact String’ result available for Intezer Analyze users)

(Strings from one of the files found when making the above string search)

We can confirm this by searching for the strings on Github and finding the specific code they used:

Creating YARA signatures from OST library strings can yield some successful threat detections, however, attackers can easily remove those strings. We have witnessed first hand these malware families removing such strings once they have recognized their mistake and we are aware of multiple other threat actors using this library without the accompanying strings.

Therefore we must find a different method to create signatures to detect the use of these libraries.

Code-based Signatures

The premise of code reuse signatures is to create YARA rules based on repeating binary patterns. These binary patterns are normalized code instructions. Normalized as in they must be readjusted to account for inconsistencies between different compilation outputs (e.g. different registers being used or varying immediate values). Each compiler has different compilation optimization rules and even the slightest difference can result in signatures becoming essentially ineffective.

To demonstrate how you can create a code-based YARA signature, let’s look at the MemoryModule library as an example. We uploaded a batch of precompiled MemoryModule binaries to Mega.nz so you can follow along.

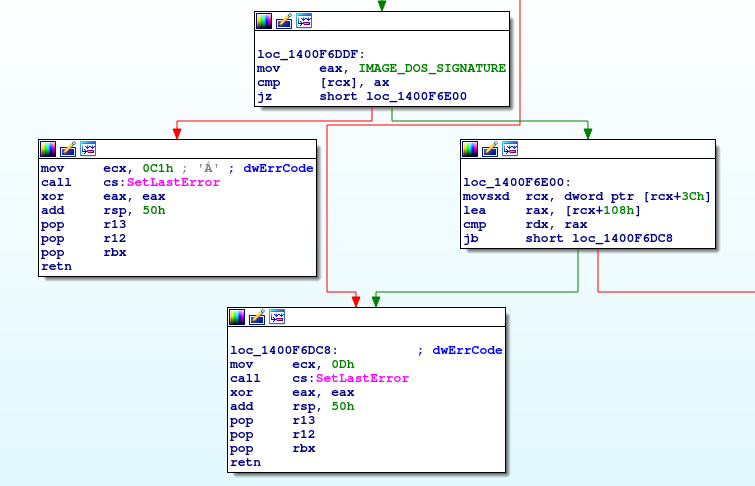

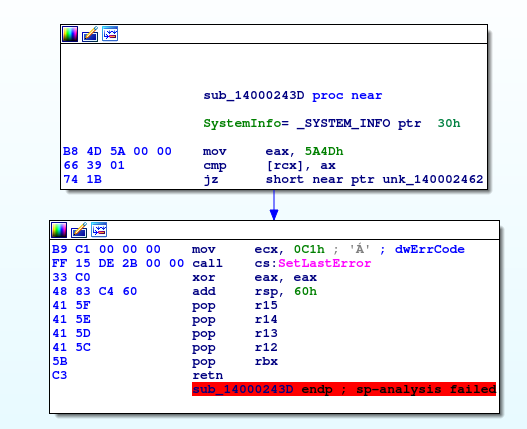

We compile the library and search for assembly code that looks unique to our library (we also generate a PDB file so that we can easily track the code). We chose the following blocks in the MemoryLoadLibraryEx function:

The blocks we will inspect specifically are the top center and middle left blocks, which can be traced to the following code:

Note: It’s also possible to do this the opposite way. First, choose the source code which seems unique and then only track the related assembly. It really depends on what is most comfortable for you.

It’s important to compile the library via several compiler versions in order to ensure the binary patterns we are signing don’t change drastically. You can find here an open source script we made available for this task. Generally, choosing small blocks with simple instructions like the ones we selected is recommended since there is less room for changes to be made through different compiler versions.

After browsing through these libraries to make certain that our code remains the same between different compiler versions, we can start building our binary YARA signature.

For the sake of brevity we rearranged the function so only the code we’re interested in appears on screen:

Using an Intel Instruction Set reference sheet, turn the first block into a binary pattern:

B8 4D 5A 00 00 => mov reg, imm32 => B? 4D 5A 00 00 66 39 01 => cmp [reg], reg => 66 39 ??

For example, mov reg, imm32 is encoded as B8+ rd in the mov command. This means the second byte has possible values 8-0xf so let’s put a question mark over it.

We avoid signing the jz instruction because it can turn to jnz on another compiler’s whim. For this reason, familiarity with compiler behavior is useful and can be attained by reviewing multiple versions of the same code through binaries created for different library versions.

Moving on to the second block, let’s turn only its beginning sequence into a binary pattern:

B9 C1 00 00 00 => mov ecx, 0C1h => B9 C1 00 00 00 FF 15 DE 2B 00 00 => call cs:offset => FF 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? 33 C0 => xor eax, eax => 33 C0

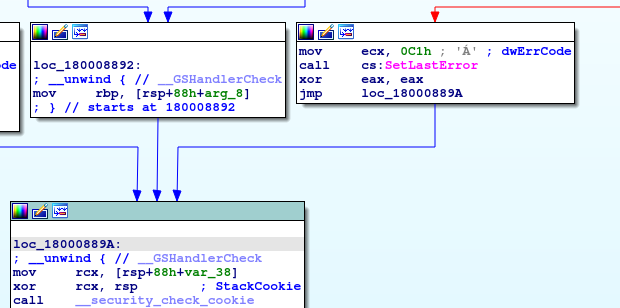

We don’t normalize mov ecx, 0C1h because it isn’t part of the function’s logic (it’s used to handle the stack frame, aka ‘the function’s infrastructure’) and as you can see below it sometimes doesn’t trail our “real” logic:

Next let’s combine the two functions into a YARA rule and add a condition for the blocks to be close to each other. We chose a distance of 0x800 bytes after reviewing the same code in newer compilers, where the blocks end up on opposite sides of the same function due to new optimizations (as can be seen in the V142/V141 versions):

rule MemoryModule_x64 { strings: // First block: $s1 = { B? 4D 5A 00 00 // mov <reg>, 0x00004D5A 66 39 // cmp <reg>, <reg> } // Second block: $s2 = { B9 C1 00 00 00 // mov ecx, 0x000000C1 FF 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? // call cs:[mem] 33 C0 48 // xor eax, eax } condition: $s1 and $s2 in (@s1..@s1+0x800) and $s3 in (@s1..@s1+0x50) and positives > 0 }

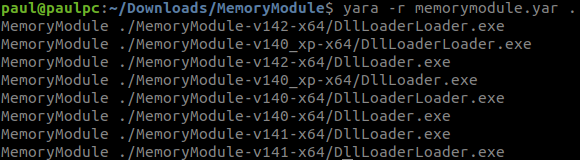

Finally we’ll test the validity of our new rule.

Let’s make sure we don’t miss any MemoryModule binaries (no false negatives):

Before deploying the signature, we test it on VirusTotal.

In this case we had to add a block to the signature (we chose the one to the right from the initial figure) to reduce false positives, as we found the 0x800 distance made the signature too generic and returned hits on programs that didn’t use MemoryModule.

The final signature looks like this:

rule MemoryModule_x64 { strings: // First block: $s1 = { B? 4D 5A 00 00 // mov <reg>, 0x00004D5A 66 39 // cmp <reg>, <reg> } // Second block: $s2 = { B9 C1 00 00 00 // mov ecx, 0x000000C1 FF 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? // call cs:[mem] 33 C0 48 // xor eax, eax } // Third block: $s3 = { 48 63 ?? ?? // movsxd <reg>, dword ptr [reg+0x3C] 48 8D ?? 08 01 00 00 // lea <reg>, [reg+0x108] 4? ?? ?? // cmp <reg>, <reg> } condition: $s1 and $s2 in (@s1..@s1+0x800) and $s3 in (@s1..@s1+0x50) and positives > 0 }

Conclusion

Malware developers often incorporate open source libraries in order to cut costs and preserve their research and development resources for other activities. In this article we presented how you can create signatures to target malware that outsource their offensive capabilities to these libraries. We demonstrated why signatures based on strings can be easily broken when hunting for these projects and how you can create more advanced code-based signatures to catch malware that incorporate OST libraries.

We hope this post was productive for you and wish you happy hunting! We invite you to virtually attend the talk which will present the full research study at VirusBulletin.

The Intezer Analyze enterprise edition generates code-based YARA signatures for any detected threat similar to the signature detailed in this post. Learn more