Large scale cyber attacks seem to be happening once a month these days. Originally discovered by ESET (https://www.welivesecurity.com/2017/10/24/kiev-metro-hit-new-variant-infamous-diskcoder-ransomware/), Ukrainian and Russian organizations have been hit with the latest ransomware attack named Bad Rabbit. At the time of writing this post, the ransomware has believed to have originated from compromised webpages with a fake popup for updating Adobe Flash Player. It has been reported that much of the behavior of Bad Rabbit has been similar to a previous ransomware known as NotPetya.

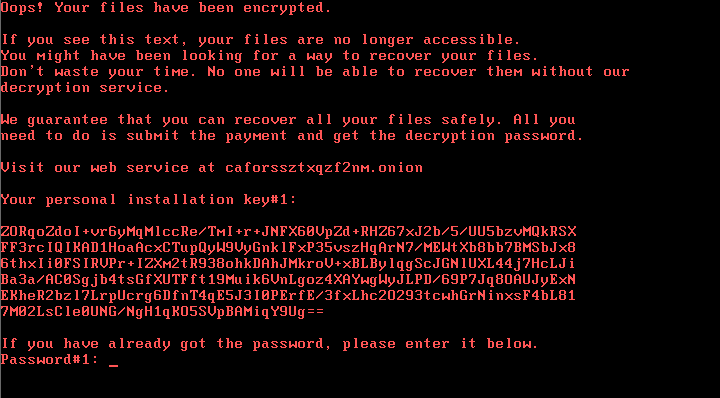

(screenshot from ESET report, after ransomware has infected a computer)

Using Intezer Analyze™, we have found code reuse from NotPetya throughout different binaries of Bad Rabbit.

The Bad Rabbit loader, with the original name (install_flash_player.exe) and metadata (Adobe Systems Incorporated as the company and Adobe Flash Player Installer/Uninstaller), was made to look like the Adobe Flash Player installer. You can see in the screenshot below that according to our analysis, the binary did not contain any code from any Adobe product but does contain code from NotPetya. In fact, we find that 27% of the code in the loader has been seen in only NotPetya samples. Find the public report here (https://analyze.intezer.com/#/analyses/6ba279af-8ce2-46c6-8b86-5fa65a5ed42a)

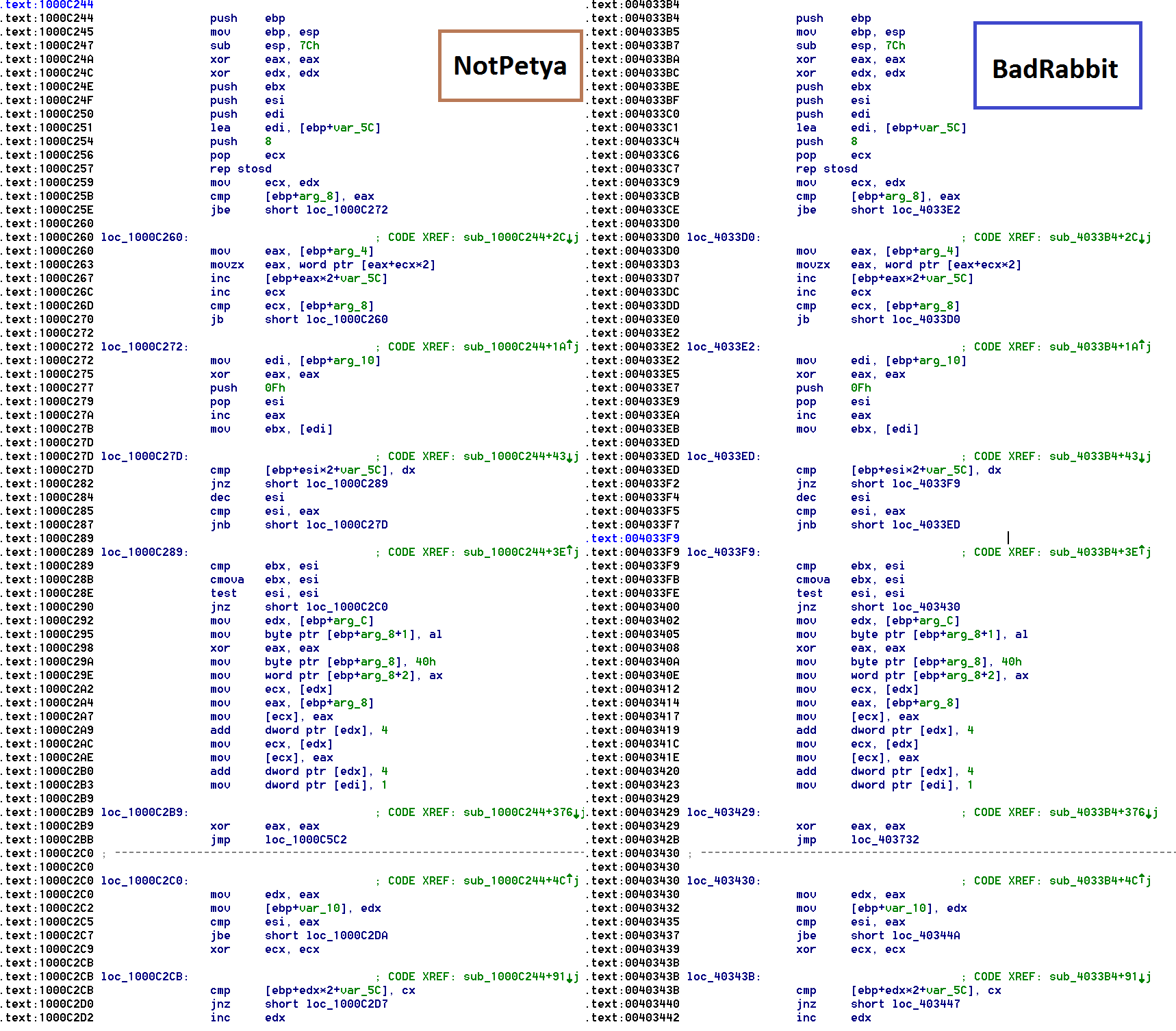

Below is a direct comparison of function (0x1000C244) of NotPetya (027cc450ef5f8c5f653329641ec1fed91f694e0d229928963b30f6b0d7d3a745) and function (0x4033B4) of the Bad Rabbit loader (630325cac09ac3fab908f903e3b00d0dadd5fdaa0875ed8496fcbb97a558d0da).

Another example of code reuse in the loader from a function that seems to initialize some type of struct.

#BadRabbit (#NotPetya v2) unpacked DLL: infpub.dat : https://t.co/Ey5Yffsn74

— hasherezade (@hasherezade) October 24, 2017

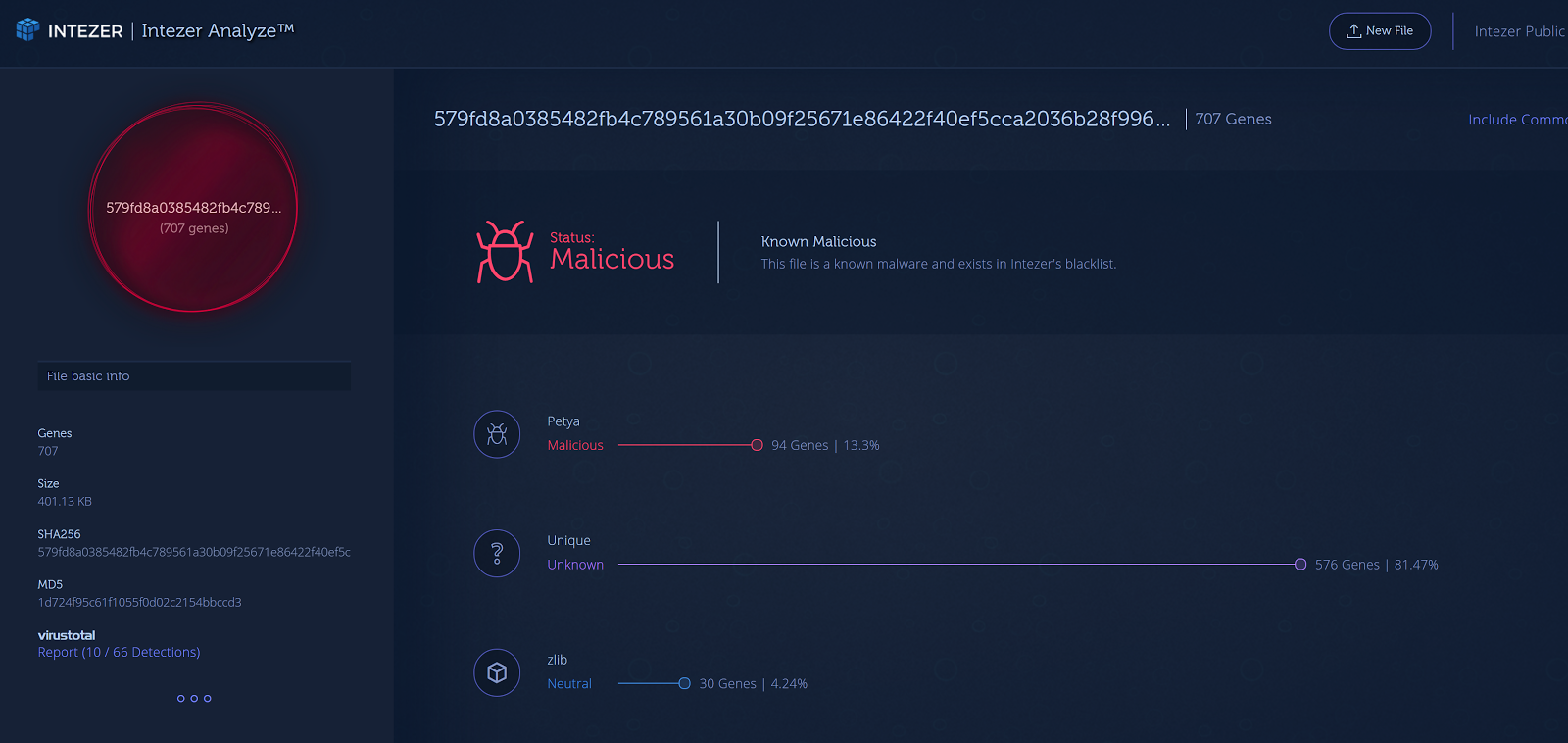

The final module that gets loaded and is responsible for encrypting the files on disk (579fd8a0385482fb4c789561a30b09f25671e86422f40ef5cca2036b28f99648) also has a code connection with NotPetya samples. According to our technology, we can see that 13% of the code has been reused. You can find the public report here. (https://analyze.intezer.com/#/analyses/d41e8a98-a106-4b4f-9b7c-fd9e2c80ca7d)

#badrabbit found to have 13% code reuse of #notpetya #petya

here's a public report with the unpacked sample: https://t.co/NOIul4yLVT— Jay Rosenberg (@jaytezer) October 24, 2017

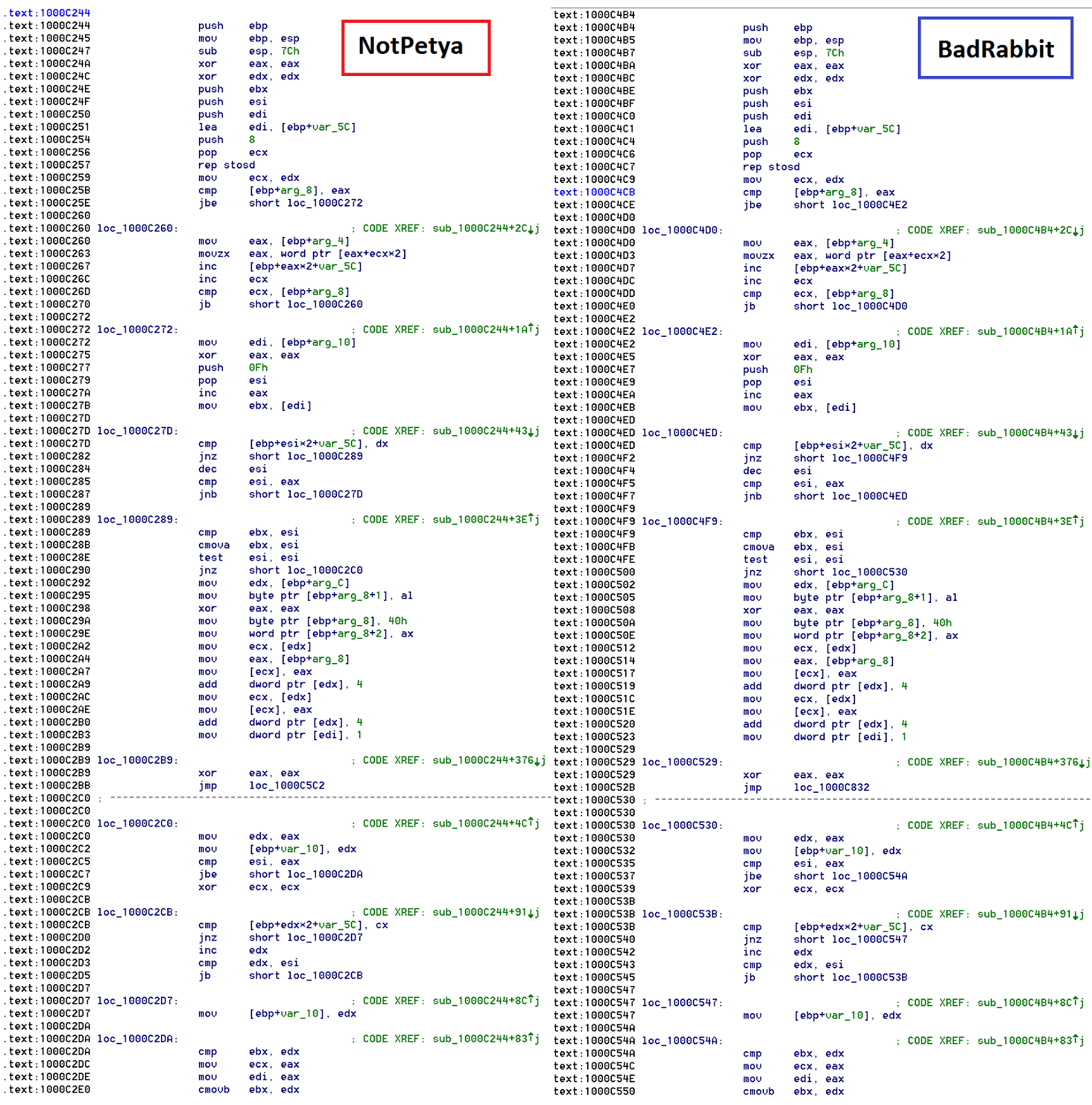

Below is a screenshot comparing a function (0x1000777B) of NotPetya (027cc450ef5f8c5f653329641ec1fed91f694e0d229928963b30f6b0d7d3a745) and a function (0x1000733C) of the encryptor module of Bad Rabbit (579fd8a0385482fb4c789561a30b09f25671e86422f40ef5cca2036b28f99648).

The next screenshot is of another matching function between the two samples.

As you can see in this attack, and in many other cases, malware authors constantly reuse their code. By recognizing code reuse, you force malware authors to rewrite code and come up with new techniques to avoid detection. This changes the playing field and makes it far less cost effective for malware authors and cyber crime organizations.

IOCs:

630325cac09ac3fab908f903e3b00d0dadd5fdaa0875ed8496fcbb97a558d0da

8ebc97e05c8e1073bda2efb6f4d00ad7e789260afa2c276f0c72740b838a0a93

579fd8a0385482fb4c789561a30b09f25671e86422f40ef5cca2036b28f99648