Linux threats are becoming more frequent and a more common type of Linux threat is cryptojacking, which is the unauthorized use of an IT system for the purpose of mining cryptocurrency. While cryptominers are well-documented, it’s not often that you get an inside look. It’s rare to see the dashboard of the wallets being used in an active cryptojacking campaign with dozens of victims, as well as the attacker’s profit margin.

This post details an ongoing cryptojacking campaign targeting Linux machines, using exposed Docker API ports as an initial access vector to a victim’s machine. The attacker then installs a Golang binary, which is undetected in VirusTotal at the time of this writing.

The file serves as a Monero cryptominer installer and sets up configuration for the miner. The attack uses SSH to maintain superiority on the victim’s machine, leaving a backdoor and installing its own SSH keys on the host.

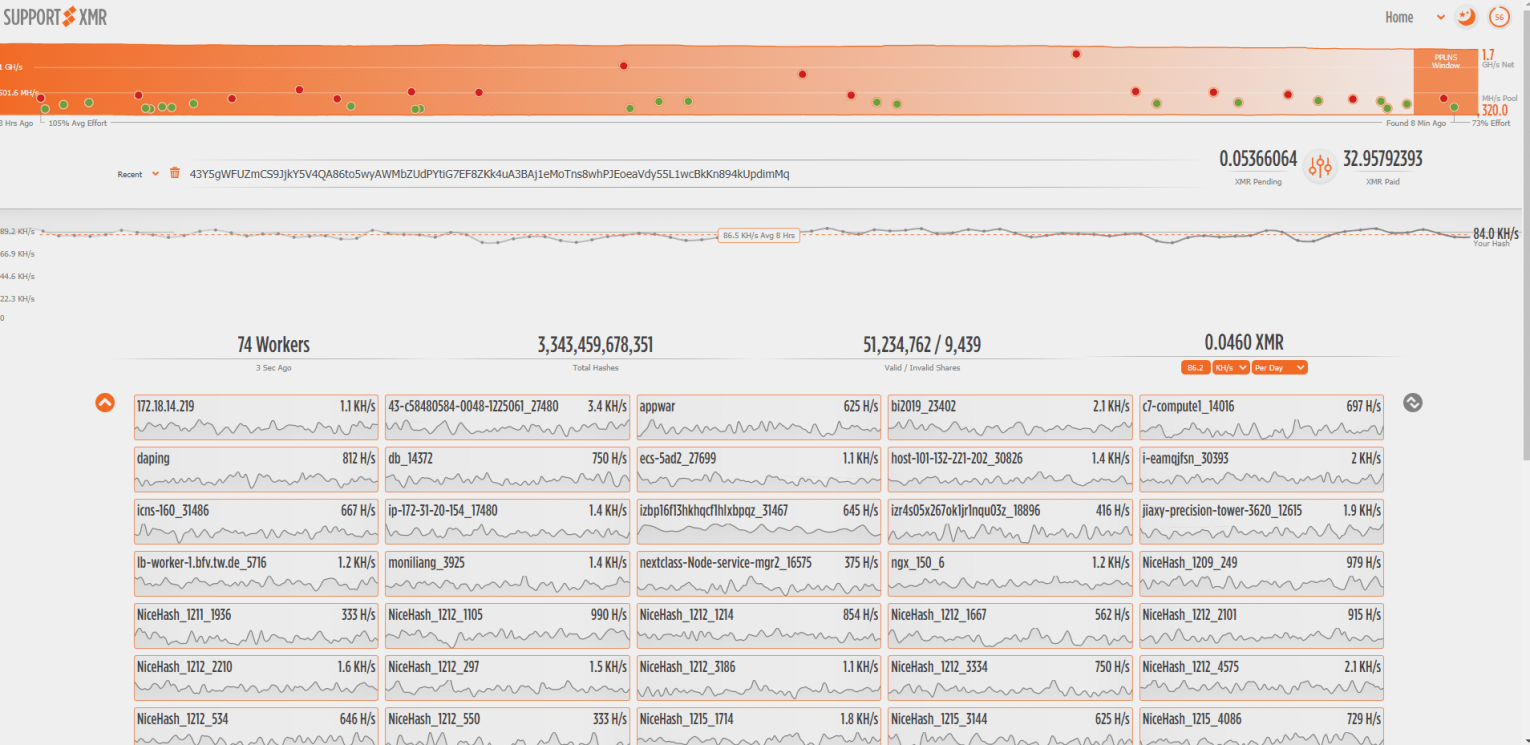

This cryptojacking campaign has been active for nearly a year. We are certain that each day at least one payment is passed into two wallets and there are currently 95 workers. Workers are victim machines whose resources are being used to mine cryptocurrency for the attacker. A snapshot of the active workers is shown in Figure 1.

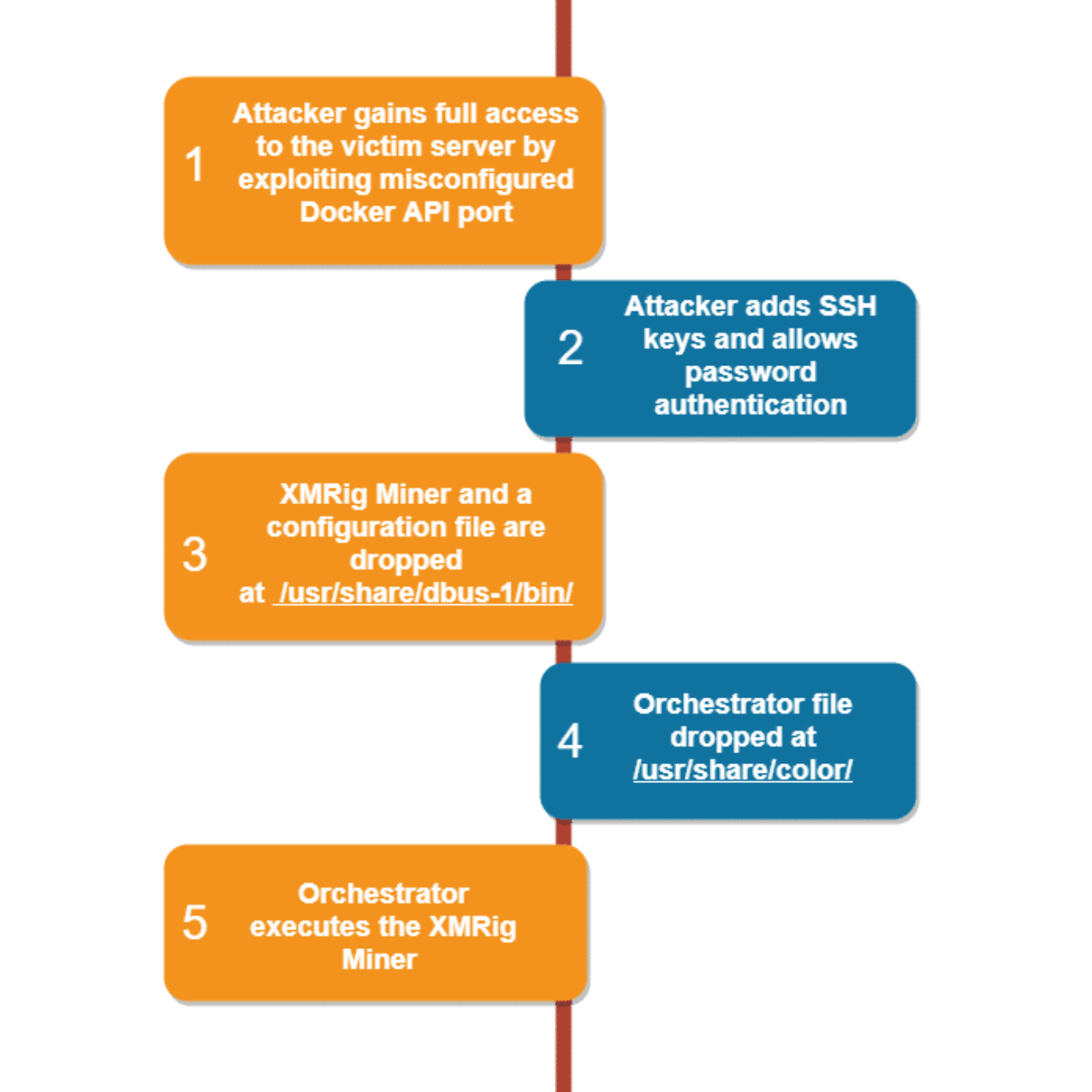

Cryptojacking Campaign Attack Flow

A new attack flow takes advantage of a known Docker misconfiguration, putting the host at risk for being compromised. The attacker exploits this misconfiguration to gain full control over the Docker daemon and creates a new container with access to the host’s filesystem. With access to the filesystem, the attacker installs malware on the Docker host.

First, the attacker establishes a stable SSH connection by adding their own SSH key to the host and editing the configuration of the SSH service to allow password authentication. These modifications remove dependency on the misconfiguration, giving the attacker a stable connection to the victim.

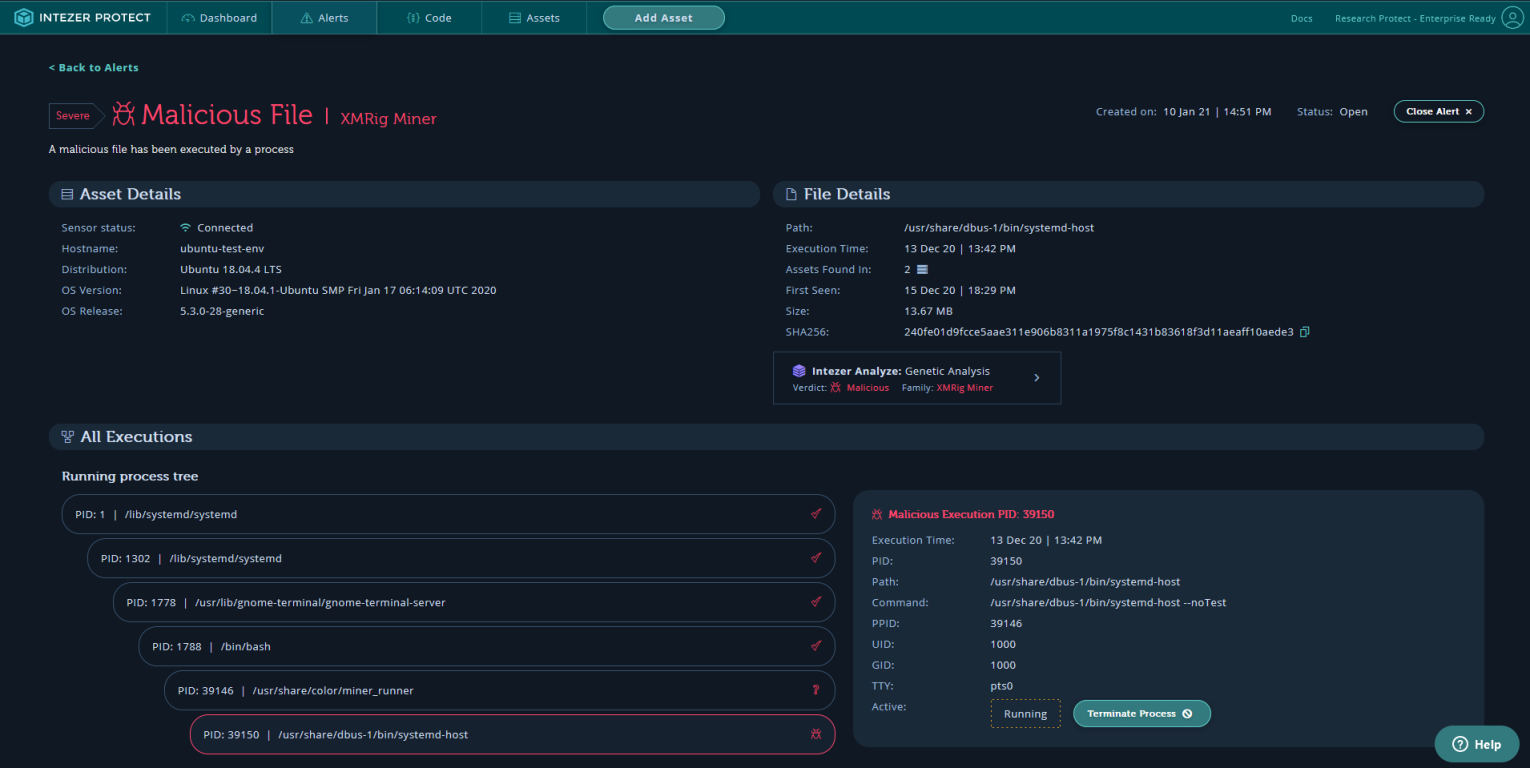

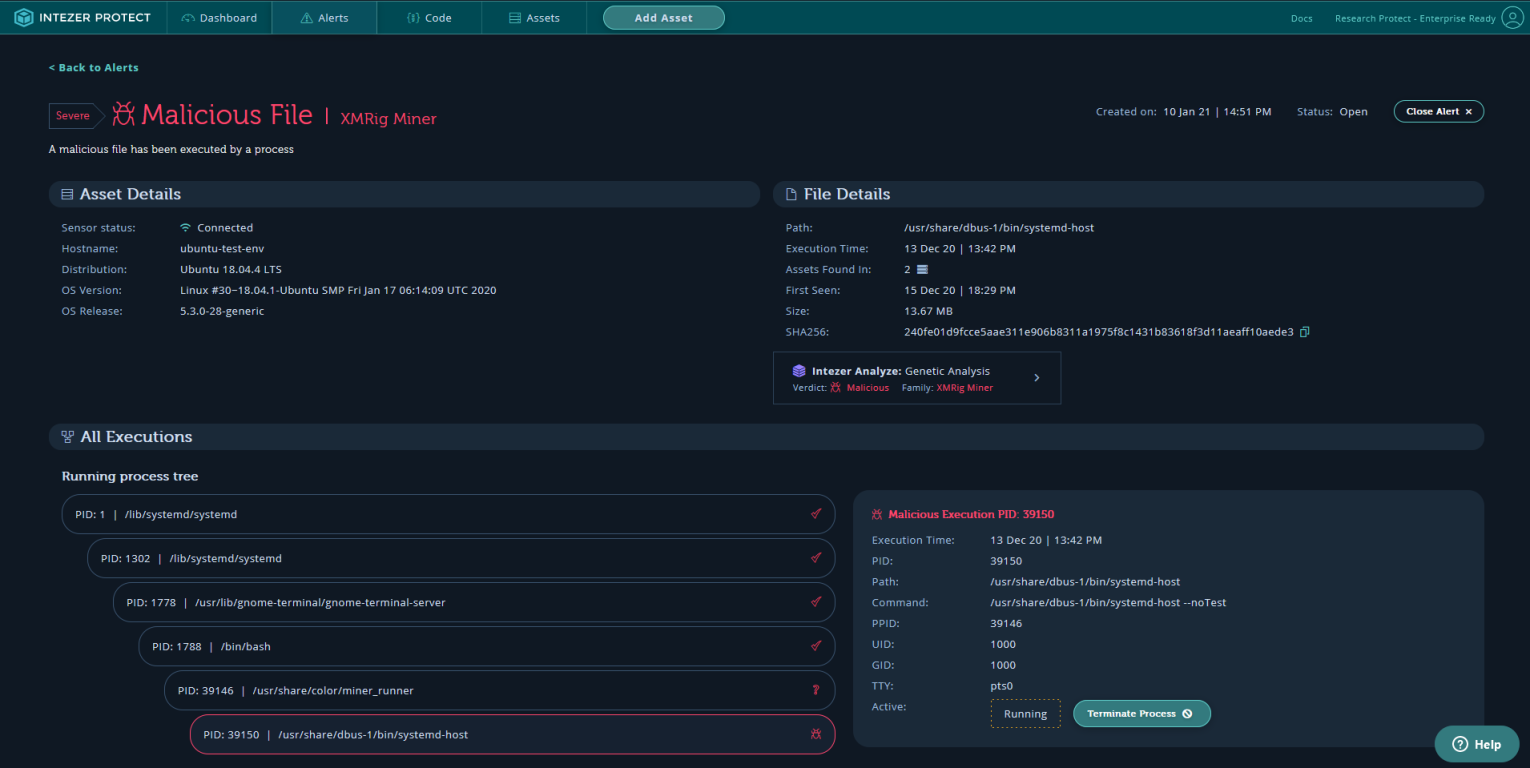

Next, they install two binary files on the host: an XMRig Miner at location /usr/share/dbus-1/bin/ and an orchestrator file at /usr/share/color/. We analyzed this file and came to the conclusion that it’s being used to execute XMRig Miner and to ensure it keeps running.

The orchestrator is responsible for preparing and initializing configurations for the execution of the coinminer malware. Before running the coinminer, it verifies the path /usr/share/dbus-1/bin contains two files: systemd-host (aka the miner) and the other named IBus, the miner’s configuration file.

The path /usr/share is not commonly seen in Linux malware and is writable only with root privileges. The path /tmp is more often seen as an installation path in Linux malware since it does not require root privileges. The attacker has root privileges because the container they escaped from has them and hence the attacker has access to /usr. Placing the files at /usr may imply that they are taking advantage of the high privileges they have in order to use this path as some sort of hiding technique that is harder to detect.

The configuration file reveals interesting insights about the miner and the cryptojacking attack campaign. From the configuration we can tell that the target cryptocurrency is Monero, known to be more private than other coins like Bitcoin. This means that the details of the transaction amounts and the sender/recipient identities are disguised. In addition, we found the address of the pools and the IDs of two wallets used in this campaign. The address of the pools belongs to supportxmr domain and the wallets are still active at the time of this publication.

Take a Look (or Two) at the Dashboards

It’s rare to find an active wallet with victim information for a few reasons. Management of the wallets is taken care of by another server that acts like a proxy so that the malware connects without providing the wallet. In some cases, the wallets are not active or have only a few workers. In this recent attack, we found a live dashboard—shown in Figure 3— that is constantly updated with new workers and paints the full picture of this campaign.

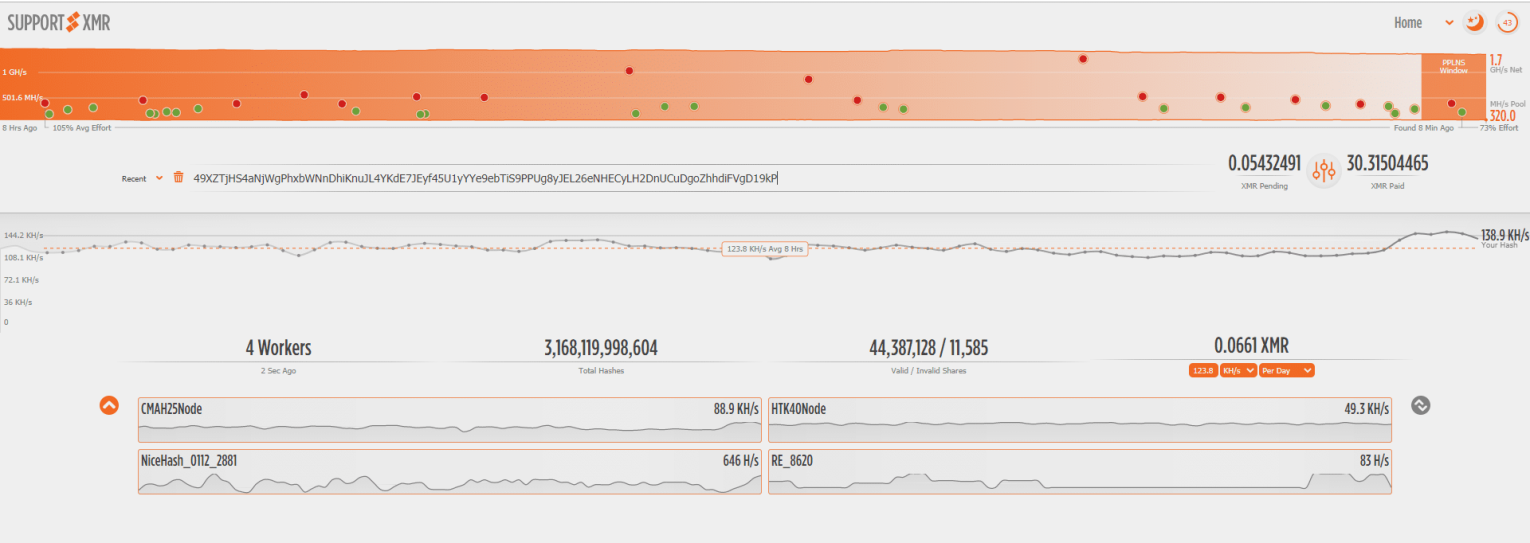

The dashboard shows that this cryptojacking campaign has been active for almost a year with both wallets receiving at least one payment per day. One of the wallets averages 95 workers while the second wallet averages four workers, meaning the campaign is still operational and has about 100 victims to date.

Insights About the Cryptojacking Victims

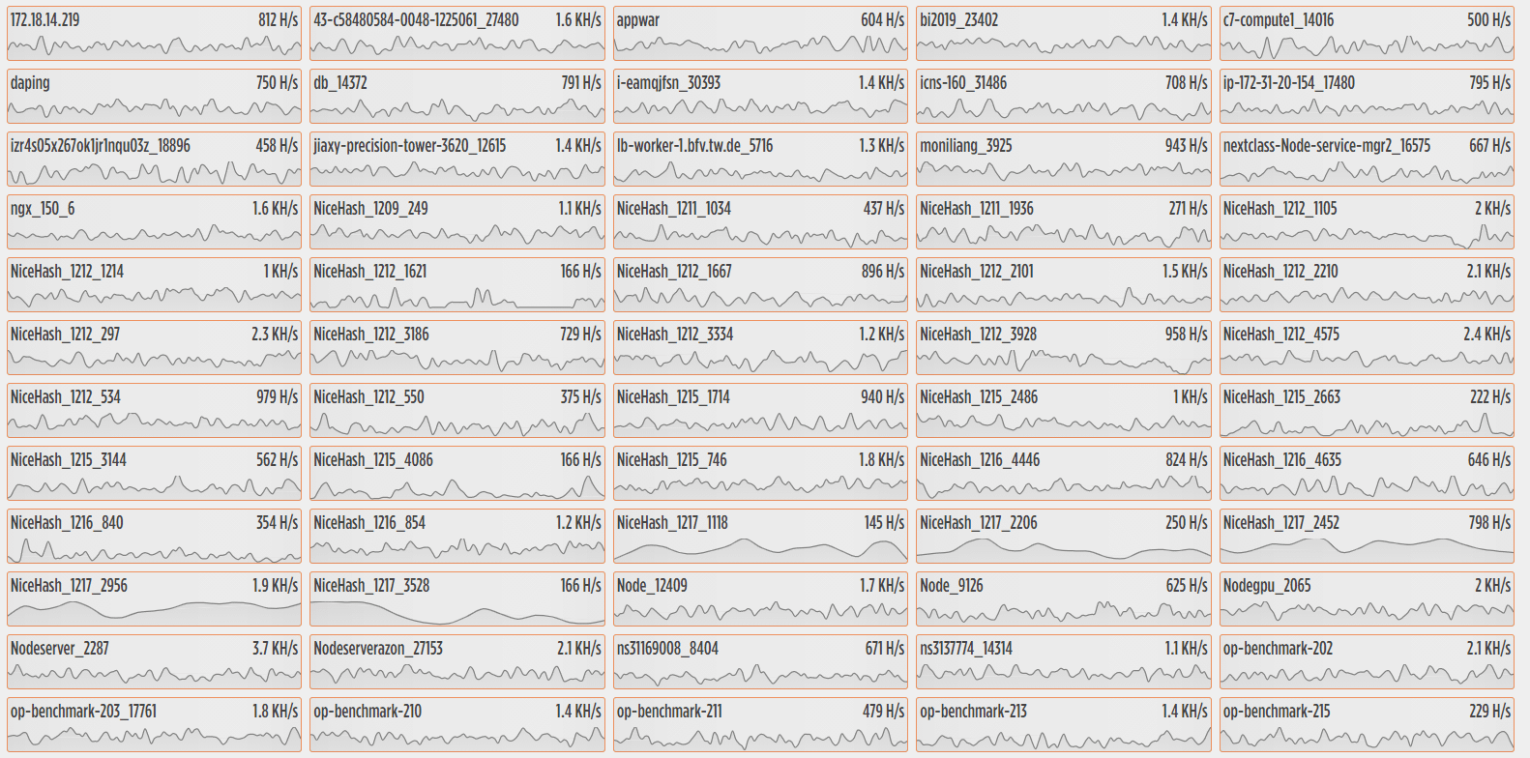

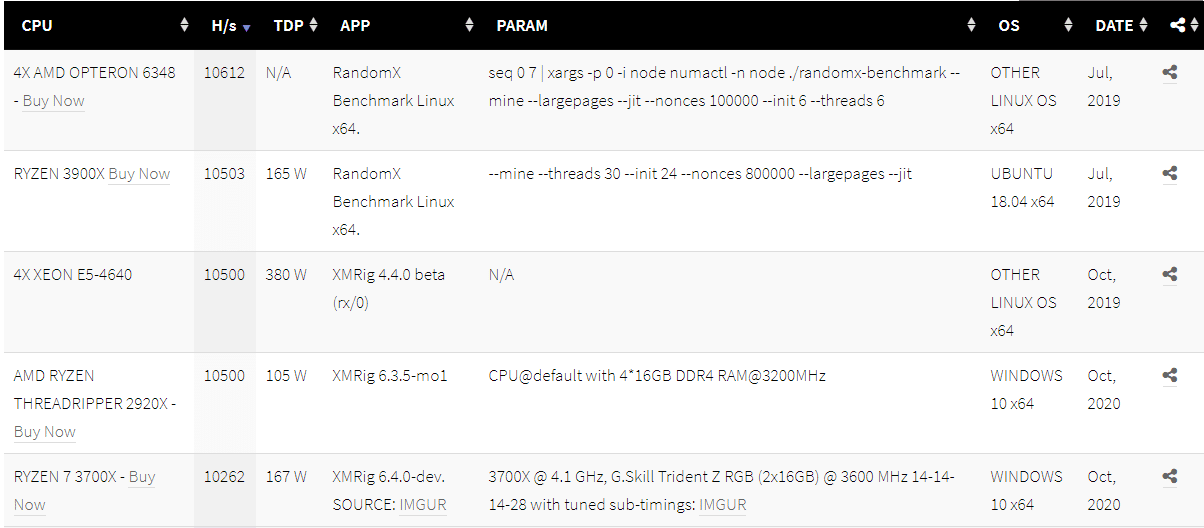

Using the randomx CPU benchmarks, we can cross-reference the hash rates seen in the dashboard (Figure 4) with the CPU type that generates them as shown in Figure 5. From this comparison we can see that most of the victims are not machines with high levels of performance but rather standard hosts similar to your home computer. But if we examine the rates from the wallet that has only three workers, we can infer its workers have more computing resources than those in the other wallet given their CPU power.

It’s possible that the attacker uses different wallets to separate high and low performance victims.

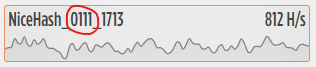

We examined the workers’ names. Some of them contain a string that looks like a date, which we assume is the date of infection. In Figure 6, for example, the marked numbers can be translated into 01/11, or January 11.

Cryptojacking Mitigation

Fix your Misconfigured Docker API Port

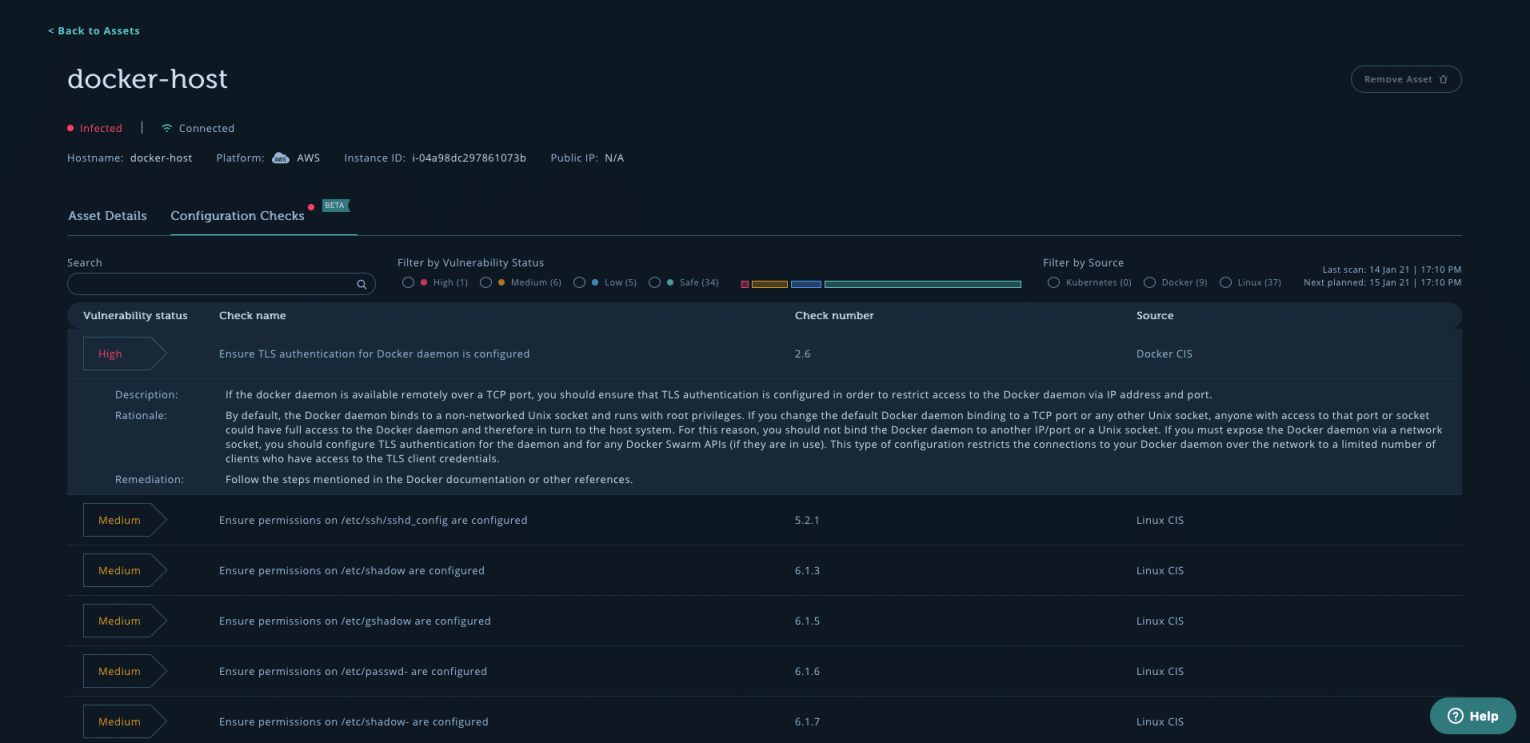

Misconfiguration of the Docker API port is one of the most common yet deadly mistakes users can make. Fortunately, this cryptomining operation can be easily avoided just by having a secure configuration.

Docker Security Best Practices

Our article here provides a checklist of Docker security best practices, from development and deployment onto the production environment. In addition, you can verify that other misconfigurations do not pose a risk to your environment via lateral movement by referencing this list of Docker misconfigurations.

Intezer Protect for Cloud Workload Protection

Advanced attacks like SolarWinds and Pay2KEY have shown that focusing only on vulnerabilities in your own code is not enough to secure your environment. It’s time to assume breach and detect and respond to attacks when they occur in production.

Intezer Protect is a Cloud Workload Protection Platform designed to protect Linux machines in runtime against unauthorized code. With Intezer Protect you can easily detect cryptominers and other threats in your cloud, as well as identify the misconfiguration that could have been exploited — in this case, in Docker.

Executing the orchestrator file will prompt an immediate alert in Intezer Protect as seen in Figure 8.

When XMRig Miner is executed by the first file, Intezer Protect will trigger a second alert as seen in Figure 9.

The Bottom Line

The threat described in this post is an example of a well-detected miner that uses SSH to maintain connection with the victim; but also leaves a “trail” that privies us to information we rarely get to see from a cryptojacking campaign.

Cryptomining malware has become a familiar threat on Linux servers because it’s relatively cheap and easy to launch. It’s not often that you get to see how profitable these campaigns can be for the attacker—with access to the wallets, how much they earned and the dashboard as the attacker sees it.

IoCs

XMRig Miner

240fe01d9fcce5aae311e906b8311a1975f8c1431b83618f3d11aeaff10aede3

Miner_installer

8ecffbd4a0c3709cc98b036a895289f33b7a8650d7b000107bafd5bd0cb04db3

Wallets’ Addresses

43Y5gWFUZmCS9JjkY5V4QA86to5wyAWMbZUdPYtiG7EF8ZKk4uA3BAj1eMoTns8whPJEoeaVdy55L1wcBkKn894kUpdimMq (mining pool: https://supportxmr.com/)

49XZTjHS4aNjWgPhxbWNnDhiKnuJL4YKdE7JEyf45U1yYYe9ebTiS9PPUg8yJEL26eNHECyLH2DnUCuDgoZhhdiFVgD19kP (mining pool: https://supportxmr.com/)

49r6Mp1fcb4fUT5FPTgaz9E47fZV7n6JiY76c4vdBZvgDm8GmWHTVYM9Azpe4MsA9oXs2RpUNPPfH7oXABr3QnwNQKaP2W7 (mining pool: https://supportxmr.com/)

43Xbgtym2GZWBk87XiYbCpTKGPBTxYZZWi44SWrkqqvzPZV6Pfmjv3UHR6FDwvPgePJyv9N5PepeajfmKp1X71EW7jx4Tpze (mining pool: https://xmr.nanopool.org)

82etS8QzVhqdiL6LMbb85BdEC3KgJeRGT3X1F3DQBnJa2tzgBJ54bn4aNDjuWDtpygBsRqcfGRK4gbbw3xUy3oJv7TwpUG4 (mining pool: https://www.f2pool.com)

47PXdhiZphNHka2K1J9udPj5Nct4zpvCRUMqwVY4Rvyxf3FLmPqyR6J68hDX4fUF65jNxJa43szPM3Ni5zDerArzSkdFp1K (mining pool: https://supportxmr.com/)

47xS7CWWZ8c7xdxBcuiqA7KLK8kRFcaLFPViKA9w3eHVe2WcKj8iaBEADzZYXGqE9sCC71cbu64qrZhZZkafzFn2VPA9xs9 (mining pool: https://minexmr.com/)